With word that Denis Villeneuve is working on a new Dune movie, I thought I’d revisit Frank Herbert’s 1965 book. I’ve read all six of the sequels as well, and read enough about the Brian Herbert/Kevin J. Anderson-authored postmortem books not to read them. For this post however, I’ll try to stick to the original.

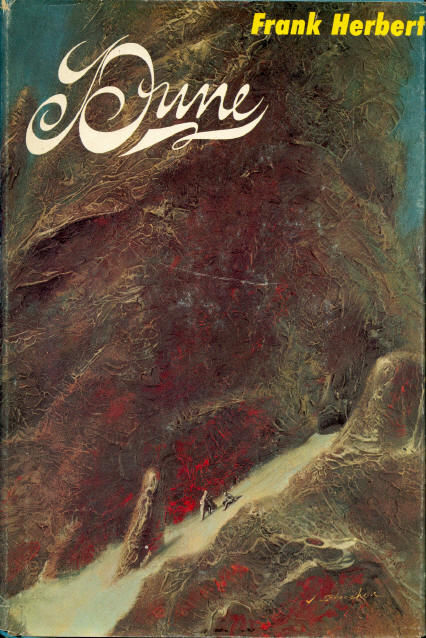

The first-edition cover, with a “dark desert” motif

Dune is surely a great work of science fiction. Frank Herbert’s writing style more than meets the “gets the job done” standard. Yes, in its bones Dune is a coming-of-age story about a young noble who must avenge himself against his father’s usurpers and assume his rightful place. But there’s nothing wrong with a healthy skeleton and Dune has much more going for it. The latter-day criticism of Dune that I’ve seen tends to revolve around Herbert’s style and diction anyway, but on a re-read I found Dune well above average in that department. I’m tempted to dismiss the critics as Ctrl-F -enabled pedants, but even granting their arguments the real allure of Dune is the setting.

Far-Future-As-Science-Fantasy had been done before, often as as a cheap trick but sometimes in a very involved manner. Certainly Jack Vance’s 1950 The Dying Earth makes use of this trope, as does The Night Land (1912) albeit in a completely different manner. The most direct influence, however, is probably Edgar S. Burroughs’ Barsoom books, beginning with A Princess of Mars in 1912. Barsoom – Mars – is a desert planet inhabited by warring cultures who mix high technology with swordplay. In A Princess of Mars, Burroughs introduces John Carter, a hero from another planet (Earth) who eventually becomes the great Warlord of Mars through the strength of his arm.

Herbert does raise the scale from planetary to interstellar, and shores up this expansion by elaborating a feudal empire populated by scheming noble houses, powerful guilds, and religious orders, tied together by the drug-fueled superluminal vessels of the radically altered Navigators. Combining textual exposition with chapter-heading epigraphs and an appendix, Herbert uses this background of an ancient space empire with no external enemies to generate and elevate the initial conflict of the story, Paul’s struggle to avenge his father. The importance of the planet Arrakis — the titular Dune — as the source of the drug melange is so great that to control it means to control the Empire (galaxy? universe? it’s never quite clear). So, Paul’s fight isn’t just a petty squabble between nobility.

Modern “bright desert” cover

In between — as Paul explores the environment and culture of Arrakis — the influence of Barsoom’s retro-heroic combat played out across endless expanses of barrenness becomes more obvious. Beyond the aesthetic, some traces of the pulps linger in Dune. Like the pulp hero John Carter, Paul Atreides is an outsider who impresses the natives with his otherworldly combat prowess. And later, at the head of his united Fremen army, Paul achieves absolute victory through transcendental violence. Herbert puts a more nuanced spin on both of these things than Burroughs, but where Dune really rises above its pulp predecessor is in the detail lavished on the setting.

Most apparent right from the beginning, Dune has a much more sophisticated view of feudal politics than the vague and idealized polities of Barsoom. More notably, Herbert devotes a great deal of attention on the ecology of the planet Arrakis. The famous sandworms, the spice, the planet’s desertification, and their impact of this on the people living on the planet. Even better, many mysteries remain about the planet at the end of the book — like the glimpses of Imperial politics, this creates the sense of a massive, living universe. (That more than anything else kept me reading the sequels when I was younger, too, and for what it’s worth Herbert generally delivered.) Herbert’s universe set Dune apart not only from the even-then decades-old pulps but from contemporary works like Smith’s Lensman series or Asimov’s Foundation, which among other things simply lacked Dune’s compelling weirdness.

Ultimately, Dune’s setting makes it great. Still, the novel has a complex and compelling story arc. At the beginning of the book, Paul is simply being raised to succeed his father. Later, he acts to avenge his father against the usurping Harkonnens. But by the time he achieves his vengeance, it doesn’t really even matter anymore. Paul’s journey has changed him so much — not least by granting him godlike powers — and so many other interests have become involved that he can’t succeed just by re-establishing House Atreides as the rightful rulers of Arrakis and loyal servants of the Emperor, much less sticking a crysknife in the back of Baron Harkonnen. Interestingly, Paul’s supernatural powers allow him not just to realize his own will, but to alter the greater historical and organizational forces impelling him (which Herbert exposits well before Paul reaches his enlightenment), while also making him deeply aware of the limits of his ability to act.

Dune’s resolution relies not only on Paul’s basically-supernatural powers but upon the combat prowess of the Fremen desert tribesmen. Dune doesn’t bother too much with specifics, but the overpowering effectiveness of Fremen armies (which easily overwhelm the most elite forces the outside universe has to offer, and in later books easily conquer the entire Empire) continues an idea Herbert developed in his other works, particularly The Dosadi Experiment: tough, isolated environments produce superior fighters, who when eventually allowed into the wider, softer world conquer all before them. While real-world parallels exist — and given the setting, the rise of Islam in the Near East is the most obvious, Paul Atreides playing the role of Mohammed — Herbert indulges in fantasy when describing the effectiveness of such hardscrabble forces. For instance, horse archery granted an enormous advantage to pre-gunpowder “barbarian” armies in much of Eurasia but such forces never made much headway in the vastly different terrain of Western Europe or Southeast Asia. But like I wrote earlier, this is an area where Dune exists mostly in the pulp realm, and at any rate the Fremen victory in Dune is much closer to Mohammad conquering Medina than Mohammed conquering China.

Dune isn’t flawless. The book trails off rather than ending properly, and anyone absolutely opposed to bildungsroman or perhaps “White Savior” narratives probably won’t make it to the end. The book is ultimately Paul Atreides’ story, and only he shows much development as a character. Killing off the outworld-ecologist-secretly-gone-native Liet-Kynes relatively early keeps his surely interesting perspective from the reader, even though it also probably cut down the book’s length and complexity. None of these flaws will prevent Dune and its world from remaining in print.

Leave a Reply