Science fiction author John C. Wright released the sixth and final book in his Count to the Eschaton series, Count to Infinity, in December. Mr. Wright is one of the few contemporary SF writers I follow, and I haven’t seen much discussion of it, so I’ll throw out my thoughts. This astonishingly ambitious series has a few flaws, but it’s overall an incredible work and deserves much more publicity than it’s gotten.

Count to the Eschaton is a six-book series spanning from a post-apocalyptic future in the 23rd century until the end of the universe billions of years later. This astronomical scale defines the series. Stephen Baxter did something similar with his Xeelee books, although Wright exceeds Baxter’s creation in every way here.

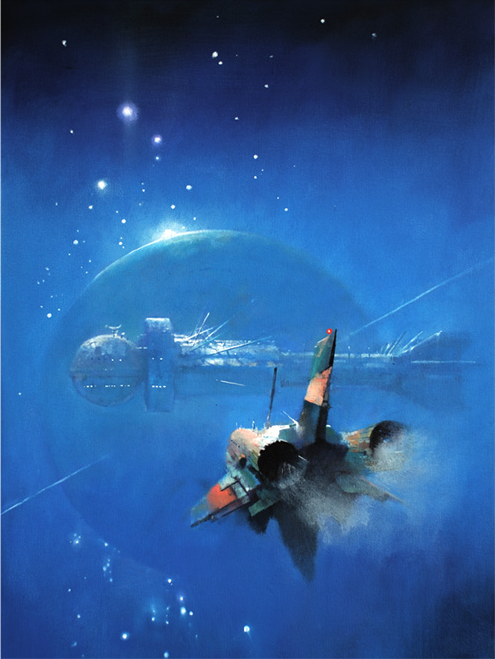

Cover art of the first book by John Harris

Because of the limitations imposed by the timeline, Wright generally uses a modified episodic format. Much gets left out; anyone reading will notice that Wright devotes a chapter or a paragraph to concepts that could sustain a novel. In this way, each of the six books is probably extensible into another six books. That the author stuck to the story he wanted to tell and told it, rather than dragging it out over years and books, speaks very well of him, particularly given the habits of some other authors in this field.

“Posthuman” intelligences are a key feature of the series. Unlike, for instance, Stanislaw Lem, Wright does not portray them as incomprehensible, although they are by default unconcerned with the goings on of baseline humans (who, in terms of scale, have about the same relation to a stellar mind as bacteria do to humans). Further, Wright believes that intelligence augmentation doesn’t alter the basic physical or moral calculus of existence. A brain whose lobes are composed of star clusters still faces the same cooperate/defect decisions as a mortal human, no matter how many technical tricks it has access to. They can go insane, experience religious epiphanies, gamble everything on desperate wars to maintain their possessions and status: in short, the Greeks were right about the ways of the gods. Wright emphasizes this, and the difference between a superintelligent being and God Himself, through one of several strokes of genius in the series: the categorization of astronomical intellects as the Choirs of Angels.

Mr. Wright is deeply versed in the historiography of science fiction and makes frequent allusions to other works in the genre. For instance, the protagonist Menelaus Montrose’s birth year of AD 2210 is almost certainly a reference to Star Trek (whose Original Series took place around 2207-2212) that also serves to contrast the Bright Future of Golden Age Science Fiction with the poor, war-torn world into which Montrose arrives. At another point in the series, the planet Jupiter is destroyed and Wright uses the occasion to subtly criticize Arthur C. Clarke’s rendering of an “ignited” Jupiter as a second sun in the sequels to 2001: A Space Odyssey. Wright’s style most closely resembles that of A.E. van Vogt, although generally more sophisticated and without van Vogt’s incoherence or humorlessness. (Wright has written an estate-authorized sequel to van Vogt’s Null-A, which I have not read.) The fifth and particularly the sixth novels seemed noticeably less well-edited than the others, although not fatally so, and Wright manages an excellent ending to the series.

The books do often have trouble keeping focus. As with van Vogt, the constantly escalating stakes account for much of this. I’d recommend someone unfamiliar with Wright’s oeuvre or modern SF in general to start with his Golden Age trilogy. I also found the main character, Montrose, rather grating. Wright’s ability to control tone prevents his writing the cardboard characters which often plague the genre – all of the major characters have distinctive voices – but Montrose’s Yosemite Sam gimmick frequently got on my nerves. Montrose is a deliberately retro-pulp character, and like his forebears serves as a vehicle to explore the setting, but that means the reader spends an awful lot of time with him. I think that rendering the fourth book, Architect of Aeons, from the point of view of the delightfully evil antagonist del Azarchel would have given the reader a break from Montrose while also allowing a more thorough exploration of several underexposed threads of the overall narrative narrative: exploration outside the Orion Arm, the crimes of Jupiter, and the continued existence of a certain character who re-emerges without proper explanation at the end of the series. Also, the relationship between Montrose and his wife is underdeveloped considering its enduring importance as a motivation throughout the series.

Still, these are minor criticisms. I haven’t mentioned even a quarter of the good things this series has going for it. Nothing else like this has been attempted, nor is it likely to be again soon. If you’re a science fiction reader, you ought to read this.

If you’re especially interested in the Huge Scale aspect of the series, you might consider reading the second book, Hermetic Millennia, first and then treating the first book as a sort of prequel.

Leave a Reply