In my review/exhortation to read of Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Short Sun, I avoided spoilers. I will not do so here, regarding my thoughts on certain details of these books.

Category: Novels Page 1 of 2

Well, I’ve done it. I’ve finished The Book of the Short Sun and, with it, Gene Wolfe’s “Solar Cycle”. It was worth it. The rest of this post will assume that you have read or are at least familiar with The Book of the New Sun. The Book of the Short Sun tells the story of a man who strives to fulfill a great vow, perhaps taken too lightly, and changes greatly because of it.

Assuming one has read The Book of the New Sun, I hope to convince you to read the rest of the Solar Cycle.

Worried about pervasive surveillance? About how much ammunition your 7th-grade MySpace posts and AIM logs will provide to the opposition when you run for office, or interview for a job? Check out the highly underrated The Light of Other Days, joint venture of science fiction giants Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter.

![The-Light-of-Other-Days-2834606[1]](https://i0.wp.com/sfoil.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/the-light-of-other-days-28346061.jpg?resize=250%2C250&ssl=1)

John Fowles’s The Magus long ago caught my eye on some Top 100 Great Novels list because I hoped it would be about a wizard in the Gandalf sense and remained intrigued by the premise when I found out otherwise. While it is indeed a Great Novel, it’s not about the Istari. However, as many things do, it got me thinking about Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun.

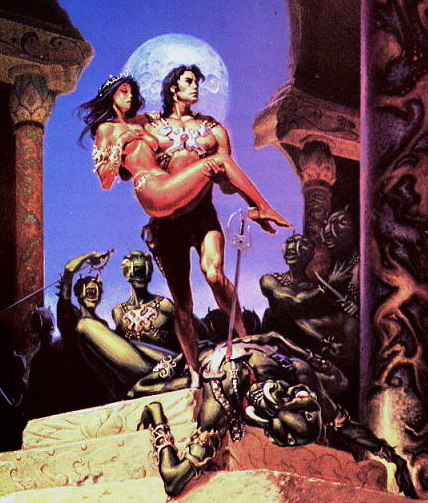

![844de8c13a4e419a07f71124aa4d341e[1]](https://i0.wp.com/sfoil.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/844de8c13a4e419a07f71124aa4d341e1.jpg?resize=297%2C444&ssl=1)

Warning: there is an image at the bottom of this post that spoils many things about both books

I’m not into military science fiction. Hammer’s Slammers? I’ve heard of it. Honor Harrington? Never read it. Some guy named Marko Kloos got into some sort of spat. A distaste for open-ended series accounts for more than a bit of my aversion, though, so if I’m going to dip my toe into the subgenre, it’s through standalone books. The three milSF books that everyone should read, so I’m told, are Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein, The Forever War by Joe Haldeman, and Armor by John Steakley.

![STRSHPTRPR1997[1]](https://i0.wp.com/sfoil.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/strshptrpr19971.jpg?resize=418%2C605&ssl=1)

Jack Vance published Araminta Station in 1988, 38 years after his first major work, the massively influential Dying Earth. Araminta Station, the first part of the Cadwal Chronicles trilogy, narrates the adventures of Glawen Clattuc, a young man of the local gentry on a wilderness-preserve planet — Cadwal — in a distant future where mankind has settled most of the galaxy in a loosely-governed “Gaean Reach”. Vance writes in his characteristic style with the assurance and deliberation of a well-earned maturity. Do I recommend it? Absolutely, although it’s not a good place to start with the author and doesn’t quite rise to the level of Vance’s immediately preceding work, Lyonesse.

Now that I’m done pontificating about the Divine Comedy, I’ll take it down a notch and look at James Blish’s modern-day occult fantasy novel Black Easter. Most reprintings collect Black Easter with its sequel, The Day After Judgment, as one work under the title The Devil’s Day. Given Black Easter’s abrupt ending — I hesitate even to call it a cliffhanger — the Devil’s Day format is the best package. Although the tale goes a little flat in the second half, if “modern-day occult fantasy” sounds like something you would be interested in, you will like this book.

Cover of the combined version. Fairly tame by the standards of Baen.

The Three Body Problem and John C. Wright’s Count to a Trillion are both about humanity confronting imminent invasion by highly advanced aliens. However, Liu is an Atheist Chinese and Wright is a Christian American, so things don’t go quite the same way in the two stories.

I will point out one significant technical difference. The Trisolarans in 3BP will arrive from Alpha Centauri in 400 years, while the much more massive Hyades Armada spends a leisurely 10,000 years en route to Earth. Eschaton’s characters acknowledge that maintaining a single continuing civilization on this time scale is preposterous, something that 3BP’s characters don’t (think they) need to worry about.

Wright’s characters are much more proactive in attempting to control their destinies than Liu’s. Fatalism, not to say nihilism, dominates the worldview of the characters in Liu’s series. Ye Wenjie and the ETO betray humanity because she wants to see the world burn; Del Azarchel and the Hermeticists do it because they want power. Both Azarchel and Montrose refuse to give up their attempts to assert their will against the powers of the heavens.

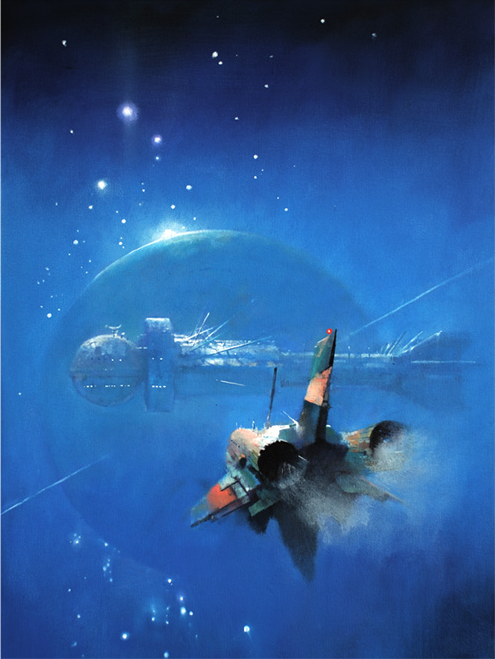

Science fiction author John C. Wright released the sixth and final book in his Count to the Eschaton series, Count to Infinity, in December. Mr. Wright is one of the few contemporary SF writers I follow, and I haven’t seen much discussion of it, so I’ll throw out my thoughts. This astonishingly ambitious series has a few flaws, but it’s overall an incredible work and deserves much more publicity than it’s gotten.

Count to the Eschaton is a six-book series spanning from a post-apocalyptic future in the 23rd century until the end of the universe billions of years later. This astronomical scale defines the series. Stephen Baxter did something similar with his Xeelee books, although Wright exceeds Baxter’s creation in every way here.

Cover art of the first book by John Harris