Plenty of people knew Harlan Ellison personally, I don’t have anything to add. Here’s one anecdote, courtesy of Cirsova. I’ll recommend some of his short stories to read in memoria, however.

Plenty of people knew Harlan Ellison personally, I don’t have anything to add. Here’s one anecdote, courtesy of Cirsova. I’ll recommend some of his short stories to read in memoria, however.

The Three Body Problem and John C. Wright’s Count to a Trillion are both about humanity confronting imminent invasion by highly advanced aliens. However, Liu is an Atheist Chinese and Wright is a Christian American, so things don’t go quite the same way in the two stories.

I will point out one significant technical difference. The Trisolarans in 3BP will arrive from Alpha Centauri in 400 years, while the much more massive Hyades Armada spends a leisurely 10,000 years en route to Earth. Eschaton’s characters acknowledge that maintaining a single continuing civilization on this time scale is preposterous, something that 3BP’s characters don’t (think they) need to worry about.

Wright’s characters are much more proactive in attempting to control their destinies than Liu’s. Fatalism, not to say nihilism, dominates the worldview of the characters in Liu’s series. Ye Wenjie and the ETO betray humanity because she wants to see the world burn; Del Azarchel and the Hermeticists do it because they want power. Both Azarchel and Montrose refuse to give up their attempts to assert their will against the powers of the heavens.

I read the first two books of Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos (Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion). I have been roundly advised not to continue with series, and I am not, especially after reading the end of Fall. Overall these two books deserve their relatively high reputation.

Hyperion was the stronger book, I suspect because of its episodic nature. Both are around 500 pages long, but the density of the narrative in Fall is much higher since most of the space in Hyperion is taken up by the pilgrims’ loosely connected stories. Fall was good on its own (though you’re about to hear me complain about it some more), but just didn’t maintain the same high standard of quality. Any reader who likes Hyperion will find it very difficult not to pick up Fall to resolve the cliffhanger, anyway.

I finally got around to watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 Solaris. I enjoy “deliberate” movies — Barry Lyndon is one of my favorites — so I was not bothered by the slow pace, but most viewers will be. The only part of the movie I’d ever specifically heard of — a digressive scene of Tokyo traffic which length Tarkovsky may have intended solely to justify the Motherland’s expenses in sending his crew to Japan — was a little awkward but the rest of the movie was sublime. Lem’s complaints about the adaptation are unwarranted; the director simply had a different vision in a different medium. Imagine Clarke griping about Kubrick’s film (although Lem’s novel is superior to Clarke’s 2001).

The alien ocean in Solaris remains beyond human understanding at the end of the novel. The ending of Neon Genesis Evangelion is also beyond understanding; this is not a coincidence.

Like many SF readers, I’ve read HP Lovecraft’s short fiction. Like many Lovecraft readers, I’m fascinated by his grasping portrayals of cosmic beings beyond the ken of man’s understanding but still left a bit wanting by his various idiosyncrasies, stylistic and otherwise. Fortunately, Lovecraft isn’t the last word on unknowable alien beings; for my part, I’ve found the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem to exceed Lovecraft in their portrayal.

I’ve read several of Lem’s books, but two of them in particular concern the subject under discussion: His Master’s Voice (1968) and Solaris (1961). In His Master’s Voice, government scientists attempt to decode a message from a distant star. In Solaris, a living ocean on another planet causes strange phenomena aboard a research station.

Science fiction author John C. Wright released the sixth and final book in his Count to the Eschaton series, Count to Infinity, in December. Mr. Wright is one of the few contemporary SF writers I follow, and I haven’t seen much discussion of it, so I’ll throw out my thoughts. This astonishingly ambitious series has a few flaws, but it’s overall an incredible work and deserves much more publicity than it’s gotten.

Count to the Eschaton is a six-book series spanning from a post-apocalyptic future in the 23rd century until the end of the universe billions of years later. This astronomical scale defines the series. Stephen Baxter did something similar with his Xeelee books, although Wright exceeds Baxter’s creation in every way here.

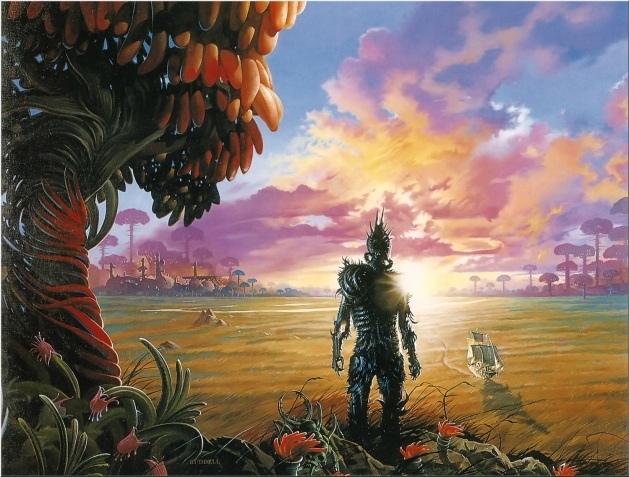

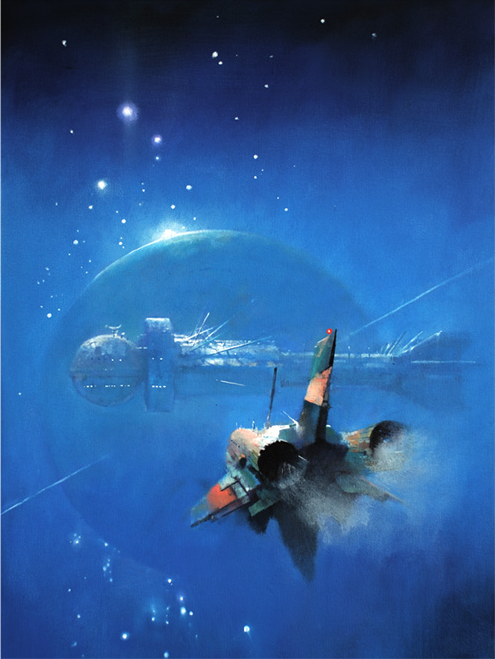

Cover art of the first book by John Harris

With word that Denis Villeneuve is working on a new Dune movie, I thought I’d revisit Frank Herbert’s 1965 book. I’ve read all six of the sequels as well, and read enough about the Brian Herbert/Kevin J. Anderson-authored postmortem books not to read them. For this post however, I’ll try to stick to the original.

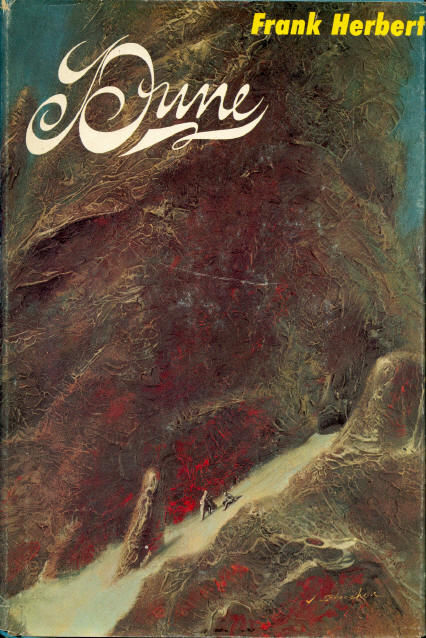

The first-edition cover, with a “dark desert” motif

Like many other SF authors, most of Cixin Liu’s characters are props for the reader to explore the setting and ideas. This isn’t helped by the characters’ Chinese names; I agree with spandrell that Chinese names just don’t trigger the proper associations for Westerners. However, Liu can produce more developed characters when necessary — for instance; he does make Ye Wenjie’s story powerful. He also manages, intriguingly, to bring to life the commissar Zhang Beihai. In many ways Zhang is a familiar type – the competent leader whom others look to in difficult situations, but…he’s a Communist political officer. Liu portrays Zhang’s devotion to “ideological work” and that work’s necessity and efficacy in a straightforward, positive manner. I find the explanation that Liu did this to atone for the sin of his brutally frank portrayal of the Cultural Revolution in The Three Body Problem tempting but inadequate. Ultimately Zhang’s job is only a mild cultural variant of the role of the priest or diversity officer.

Another notable character is Luo Ji. Luo Ji is one of five “wallfacers”, individuals granted total unquestioned authority by the United Nations, standing in for “humanity’s collective will” in typical Clarkean fashion, to do whatever it takes to forestall the Trisolaran invasion. The UN intends this tactic to counter the sophons, whose pervasive surveillance presumably doesn’t include mind-reading, at least in any useful sense. The UN selects five Wallfacers, all famous and powerful (and non-Chinese) individuals — except for Luo Ji, a burned-out grad student.

Luo Ji has no friends and, while not exactly unlucky with women, not much in the way of social or career prospects, and Liu clearly wants the reader to think he’s basically a loser. Then, as the Fifth Wallfacer, he’s handed unlimited authority and responsibility, at random. Luo Ji of course ends up being the hero, the Man Who Saves Humanity (by coming up with an effective deterrent scheme). The whole arc comes dangerously close to rehashing a particularly obnoxious trope — one pervasive in although by no means exclusive to East Asian pulp literature and comics — of the total loser who accidentally gets Power without effort and then Wins Everything, again without much effort. In raw form, this archetype is a blank reader surrogate, and Liu shows his chops by giving Luo Ji enough of a personality to be his own man, in narrative terms. He also makes the difficulties Luo faces after eating his figurative million-year mushroom rough enough to account for some real character growth, and to avoid being a straight power fantasy.

Luo Ji in Death’s End – from gramunion

Cheng Xin, whom we meet in Death’s End, is a feminine counterpart to Luo Ji who fails to maintain the human deterrent out of sheer lack of will. Both her failure and the election that determined her position as Luo’s replacement are pretty easy to read as criticisms of Western society and ideals. Chinese SF fans I’ve spoken to claim that Cheng is almost universally considered a villain in Chinese fandom. Rather than changing her ways, the story bends to fit Cheng Xin’s sensibilities, granting her first the chance to escape catastrophe through deus ex machina and at the very end by giving her a chance for sacrificial cooperation.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén